In 1606 a devastating pestilence swept through London; the dying were boarded up in their homes with their families, and a decree went out that the theaters, the bear-baiting, and the brothels be closed. It was then that Shakespeare wrote one of his very few references to the plague, catching at our precarity:

Article continues after advertisement

The dead man’s knell

Is there scarce asked for who, and good men’s lives

Expire before the flowers in their caps

Dying or ere they sicken.

As he wrote the words, a Greenland shark who is still alive today swam untroubled through the waters of the northern seas. It was, at the time, perhaps a hundred years old, still some way off its sexual maturity: its parents would have been old enough to have lived alongside Boccaccio: its great-great grandparents alongside Julius Caesar. For thousands of years Greenland sharks have swum in silence, as aboveground the world has burned, rebuilt, burned again.

I am glad not to be a Greenland shark; I don’t have enough thoughts to fill five hundred years. But I find the very idea of them hopeful.

The Greenland shark is the planet’s oldest vertebrate, but it was only recently that scientists were able to ascertain exactly how old. A Danish physicist, Jan Heinemeier, discovered a way to test lens crystallines, proteins found in the eye, for carbon-14. The amount of carbon-14, a radioactive isotope, found naturally on Earth varies from year to year; there were huge spikes during the 1960s, when mankind was at its most enthusiastic about nuclear weapons, but every period has its own carbon-14 signature. By testing the crystallines in the sharks’ eyes, it was possible to determine, very roughly, their date of birth: of twenty-eight tested, the largest, a 16.4-foot female, was reckoned to be somewhere between 272 and 12 years old. Size is thought a relatively good indicator of age, and there are records of Greenland sharks reaching 23 feet long; so it’s very possible that in the water today there are sharks who are well into their sixth century.

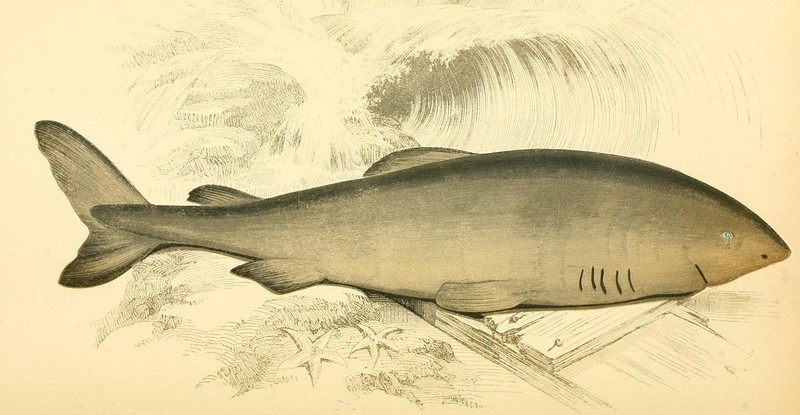

The Greenland shark is not obviously beautiful. Its face is blunt, its fins stunted, and its eyes attract a long worm like crustacean, Ommatokoita elongata. These attach themselves to the shark’s corneas, fluttering from its eyeballs like paper streamers, rendering it both almost blind and more disgusting than seems fair. It smells, too. Its body has high concentrations of urea, a necessity to ensure its body has the same salt concentration as the ocean, preventing it from losing or gaining water through osmosis, but it is a necessity that means it smells of pee—so much so that in Inuit legend, the shark is said to have arisen from the urine pot of Sedna, goddess of the sea.

The urea is also what makes it poisonous to humans when eaten fresh. If raw and untreated, the toxins in the flesh can render you “shark drunk”: giddy, staggering, slurring, vomiting. It becomes safe only if the meat is buried for several months and left to ferment, then hung out to dry for months more. Served in small chunks, and known as hakarl, it is considered, by some, a delicacy, and by others an abomination. Apparently it tastes like a very ripe cheese, left for a week in high summer in a teen age boy’s car.

The Greenland shark is slow, as befits a fish so venerable. At full speed and with strenuous effort, it moves somewhere between 1.7 and 2.2 miles per hour. Although one of the two largest flesh-eating creatures in the sea, it has an astonishingly slow metabolism; in order to survive, a 440-pound shark would have to consume the calorific equivalent of one and a half chocolate cookies per day. They are hungrier in the womb than in their waking lives: the strongest fetus develops sharp teeth, eats its siblings, and emerges into the water alone. Once born, they’re both hunters and scavengers; they have been thought to hunt seals, perhaps inhaling them as they sleep on the surface of the water, but largely they eat whatever falls off the ice: reindeer, polar bears. The leg of a man was found in one shark’s stomach, although none of the rest of him. And the Greenland shark is slow even in the process of its dying. Henry Dewhurst, a ship’s surgeon writing in 1834, saw a shark caught and killed:

When hoisted upon deck, it beats so violently with its tail, that it is dangerous to be near it, and the seamen generally dispatch it, without much loss of time. The pieces that are cut off exhibit a contraction of their muscular fibres for some time after life is extinct. It is, therefore, extremely difficult to kill, and unsafe to trust the hand within its mouth, even when the head is cut off…This motion is to be observed three days after, if the part is trod on or struck.

These slow, odorous, half-blind creatures are perhaps the closest thing to eternal this planet has to offer.

They live deep-down and secret lives. Although they have been seen at the water’s surface, they prefer to be close to the bottom of the ocean, where it’s dark and cold: they’ve been found as far down as 7,200 feet, more than seven Eiffel Towers deep. Nobody has ever seen one give birth; we have never seen them mate. Their invisibility to us also means that we do not know how endangered they are: they’re currently listed as “near threatened,” but they could be the most common sharks in the world, or urgently at risk. We do know that for some time they were overfished in large numbers—thirty thousand a year in the 1900s—in order to extract oil from their bodies. It was said that there were places in the Norwegian archipelago where houses decorated in the paint made from the shark’s liver oil fifty years ago still shone bright: a paint like no other. We know, too, that because it takes 15o years for a female to be ready to breed, they replenish slowly. They were also believed to be excellent parents: the second-century Greek poet Oppian averred that, when threatened with danger, a parent shark would open her cavernous mouth and conceal her young ones within. As this is very much, alas, not likely to be true, we will need to take care of them ourselves.

Because they live so far beyond our ships and divers, we do not know where they swim. They come to the surface only from the places where it is cold enough for them, in the Arctic, around Greenland and Iceland, but they have been found in the depths near France, Portugal, Scotland. Scientists say they may be everywhere the ocean goes deep enough and cold enough: they could be far closer to us than we think.

I am glad not to be a Greenland shark; I don’t have enough thoughts to fill five hundred years. But I find the very idea of them hopeful. They will see us pass through whichever spinning chaos we may currently be living through, and the crash that will come after it, and they will live through the currently unimagined things that will come after that: the transformations, the revelations, the possible liberations. That is their beauty, and it’s breathtaking: they go on. These slow, odorous, half-blind creatures are perhaps the closest thing to eternal this planet has to offer.

__________________________________

From Vanishing Treasures: A Bestiary of Extraordinary Endangered Creatures by Katherine Rundell. Copyright © 2024. Available from Doubleday, an imprint of Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.

Audio excerpted with permission of Penguin Random House Audio fromVanishing Treasures: A Bestiary of Extraordinary Endangered Creatures by Katherine Rundell, read by Lenny Henry and Katherine Rundell. © 2024 Katherine Rundell ℗ 2024 Penguin Random House, LLC.