If you’re not looking for it, you might miss a small illustration of the Statue of Liberty in Yolŋu leader and artist Djambawa Marawili’s 2019 eucalyptus bark painting “Americalili Marrtji (Journey to America).” The work tells the story of the events leading up to Maḏayin: Eight Decades of Aboriginal Australian Bark Painting from Yirrkala, an exhibition on view at New York’s Asia Society through January 5, 2025.

Maḏayin, translating to “sacred and beautiful” in Yolŋu Matha, features bark painting from Yirrkala, an Indigenous community in Australia’s Northern Territory with a population of about 700 people. The thin-pressed eucalyptus bark works are adorned with patterns rendered in black, white, yellow, and red pigments, which the artists said are found in clay. Some of the paintings include sacred “miny’tji” — or clan designs — that reveal the worldviews of two distinct Yolŋu moeties. The show is concluding its two-year national tour following exhibitions at museums including the American University Museum at the Katzen Center and the Fralin Museum of Art at the University of Virginia (UVA). About 16 Yolŋu artists curated the exhibition with UVA’s Kluge-Ruhe Aboriginal Art Collection, which commissioned 33 works specifically for the show.

Exhibitions of work by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander artists have gained traction at American institutions in recent years, with the largest such show in the nation’s history, The Stars We Do Not See, slated to begin its tour in October 2025 at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC. Extensive research and investigative reporting in the last decade have suggested a pattern of genocidal killings at Australia’s colonial “frontiers” through the 1920s. Indigenous Australian mothers experience higher rates of death and negative health outcomes, and last year, voters defeated a proposal to add a recognition of Aboriginal people to the constitution.

When Marawili came to the US in 2015 to view some of his own paintings in the Kluge-Ruhe Collection, a fire came into his chest, he wrote in wall text alongside “Americalili Marrtji (Journey to America).” He was doing a residency at UVA at the time, and saw other Yolŋu works in storage, hidden from view. This moment, the artists told Hyperallergic, was the catalyst for the exhibition that would unfold seven years later.

One of the results of Maḏayin is the largest published collection of Yolŋu Matha writing, which is referenced in the exhibition catalog, according to art historian and co-curator Henry Skerritt. However, long before the publication of the book, these Yolŋu stories were captured in full through the visual language of the bark paintings.

“I have always been an artist of this history,” Yinimala Gumana, one of the participating artists and a lead curator of Maḏayin, told Hyperallergic. “Our great-great-great-grandfathers told my grandfathers’ fathers until they passed it on to us. We still got that history: the message they’ve been told from the very beginning.”

According to his artist statement, Gumana’s “Dhaḻwaŋu Miny’tji (Dhaḻwaŋu Clan Designs)” (2019) recounts the story of the creator deity Barama’s influence over the Dhaḻwaŋu moiety. A couple of paintings down is “Garrapara” (2018) by Gunybi Ganambarr, who told Hyperallergic that he used glue to compact sand from the titular coastal site, a historically significant locale for the Dhaḻwaŋu moiety. The snaking, geometric patterns outline a song, he said, which takes hours to sing. Ganambarr added that he carved an exact outline of the Garrapara coastline at the top of the piece.

On the wall where Gumana and Ganambarr’s pieces hang, the paintings read like a map from left to right, from freshwater to saltwater coasts of Yirrkala.

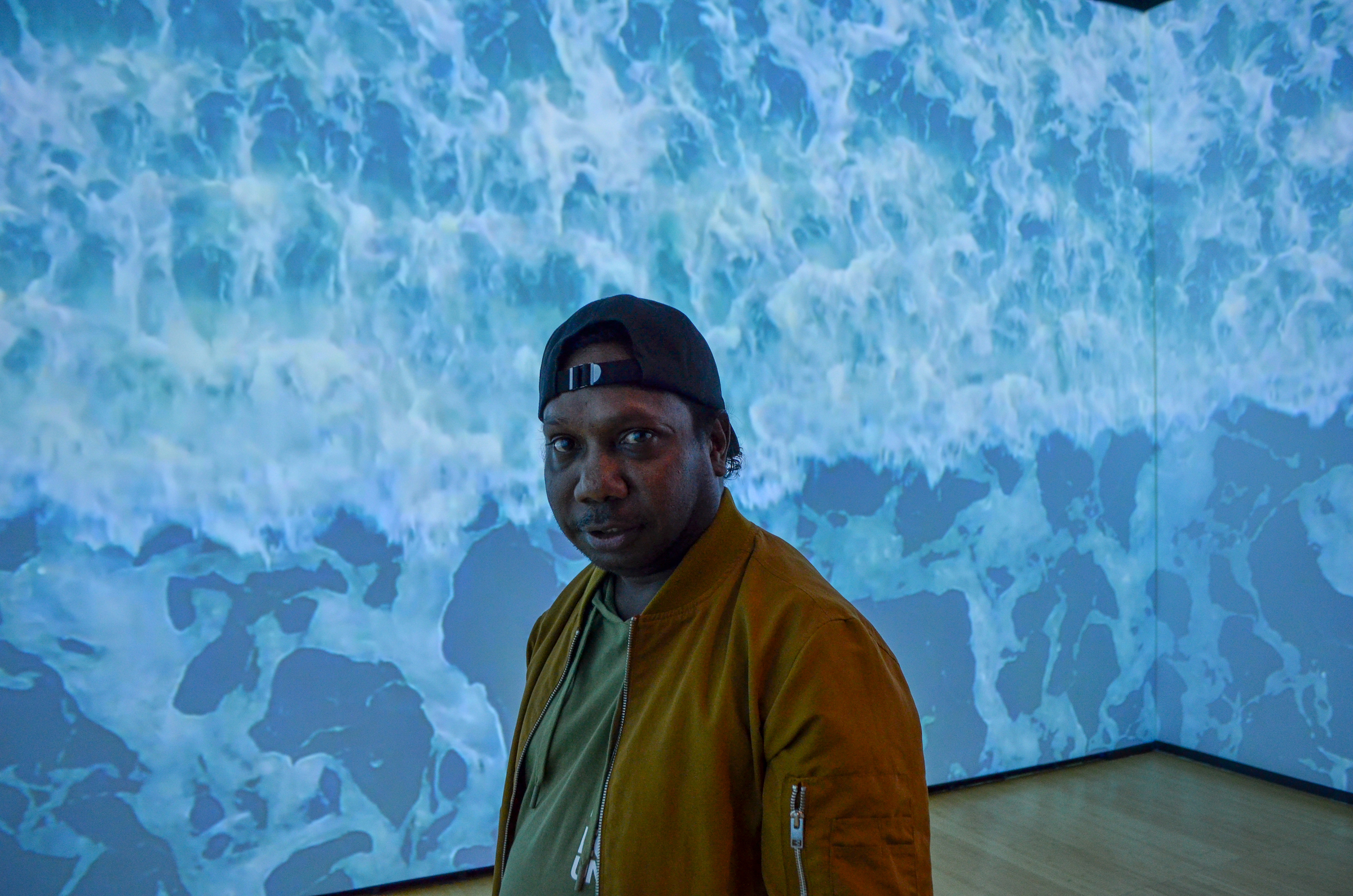

Nearby, Yolŋu documentary filmmaker Ishmael Marika’s cinematic catalogs of song and dance accompany and complement this visual history.

“We have to bring the life, the videos, and the song lines to go with the paintings, to keep them alive,” Marika told Hyperallergic.

In one such mixed-media installation entitled “Gapu Muŋurru ga Baḻamumu Mirikindi (Deep Waters of the Dhuwa and Yirritja Moieties)” (2022), Marika and his production company, the Mulka Project, overlaid a tape of ocean currents with recordings of Yolŋu ceremonial songs. The oldest Yolŋu painting in the exhibition, Woŋgu Munuŋgurr’s 1935 “Maḏayin Miny’tji” sits encased in the same room.

“It is very important to show these old paintings alongside contemporary works, to recognize that we Yolŋu have enduring patterns that connect us to our Country. I am proud to make this connection to the United States,” Marawili said in an artist’s statement.

“What follows is reconciliation and the passing knowledge to America through our art,” he continued. “Because art is important to us. It represents our mind and our soul.”