HUDSON, New York — I first saw Evan Halter’s fastidious trompe l’oeil paintings in 2014 at the Mason Gross School of the Arts at Rutgers University, where he was earning his MFA and I was teaching. By this time, he was already mixing together a section of a classical painting with something seen from the real world, such as a plumb bob. After he graduated, I visited his studio a handful of times. I was particularly intrigued by the idiosyncratic nature of his project, which includes a deep devotion to Northern and Italian Renaissance art as well as modernist collage. With this in mind, I was sure not to miss his solo exhibition, Specificities, at Turley Gallery.

Among the exhibition’s 15 works, the undated painting “Bouquet (After Ambrosius Bosschaert)” hangs on the wall opposite the collage “Bouquet Study (After Ambrosius Bosschaert),” suggesting that Halter’s paintings are based on collages for which he has superimposed a sheet of paper with cut openings over a reproduction of a painting. While the “shadows” cast by the cut paper and the “illusion” of space between the layers is always carefully rendered, I found it interesting to see what changes he had made. In this case, the painting is slightly more than three times the size of the collage.

Why is Halter interested in this kind of peekaboo seeing? In the press release, he states:

My goal is for the work to occupy a space in which it can recontextualize these familiar historical artworks, and at the same time, create something new that can act as a means to highlight the quiet and often overlooked moments in both art and life.

Halter achieves this goal, but more than this happens in the best of his paintings. Known as one of the first artists to present floral still life as a distinct genre, Bosschaert painted symmetrical, scientifically accurate bouquets. It’s this accuracy that fascinates Halter; he wants to attain a paradoxical moment when the viewer is both fooled by and aware of his deception.

I found “Bouquet (After Ambrosius Bosschaert)” to be at once frustrating and pleasurable. I could see what Halter was up too, but, at the same time, the cutout sections of paper made it impossible to grasp what the entire bouquet looked like; this impossibility seems to be one of his preoccupations. A meticulous painter who seems capable of copying a baroque work with remarkable accuracy, I think Halter knows that being able to convincingly recreate the style of a classical master is not enough. By bringing in trompe l’oeil effects, he appears to simultaneously undercut and celebrate his own deftness. But this is not the main reason I have followed the artist for the past decade.

The undated paintings “One to One (The Draughtsman of the Lute by Albrecht Dürer)” and “Chalice (After Albrecht Dürer and The Master of the Morrison Triptych)” reveal two sides of the artist. In the former, he transforms a woodcut measuring around five by seven inches into a slightly larger oil painting (eight by ten inches). Based on a reproduction, Halter’s intimately scaled painting comes across as a venerable homage, a vulnerable object, whose purpose might be talismanic, and an embodiment of yearning. More than just an expression of the artist’s subjectivity, it is a lament for all the knowledge of painting that has been lost to us, from the desire for accuracy and precision that occupied Bosschaert and Dürer to the recognition that nostalgia is part of being a still-life painter. In this sense, Halter’s use of collage is about loss and our inability to see the actual world in all its complexity.

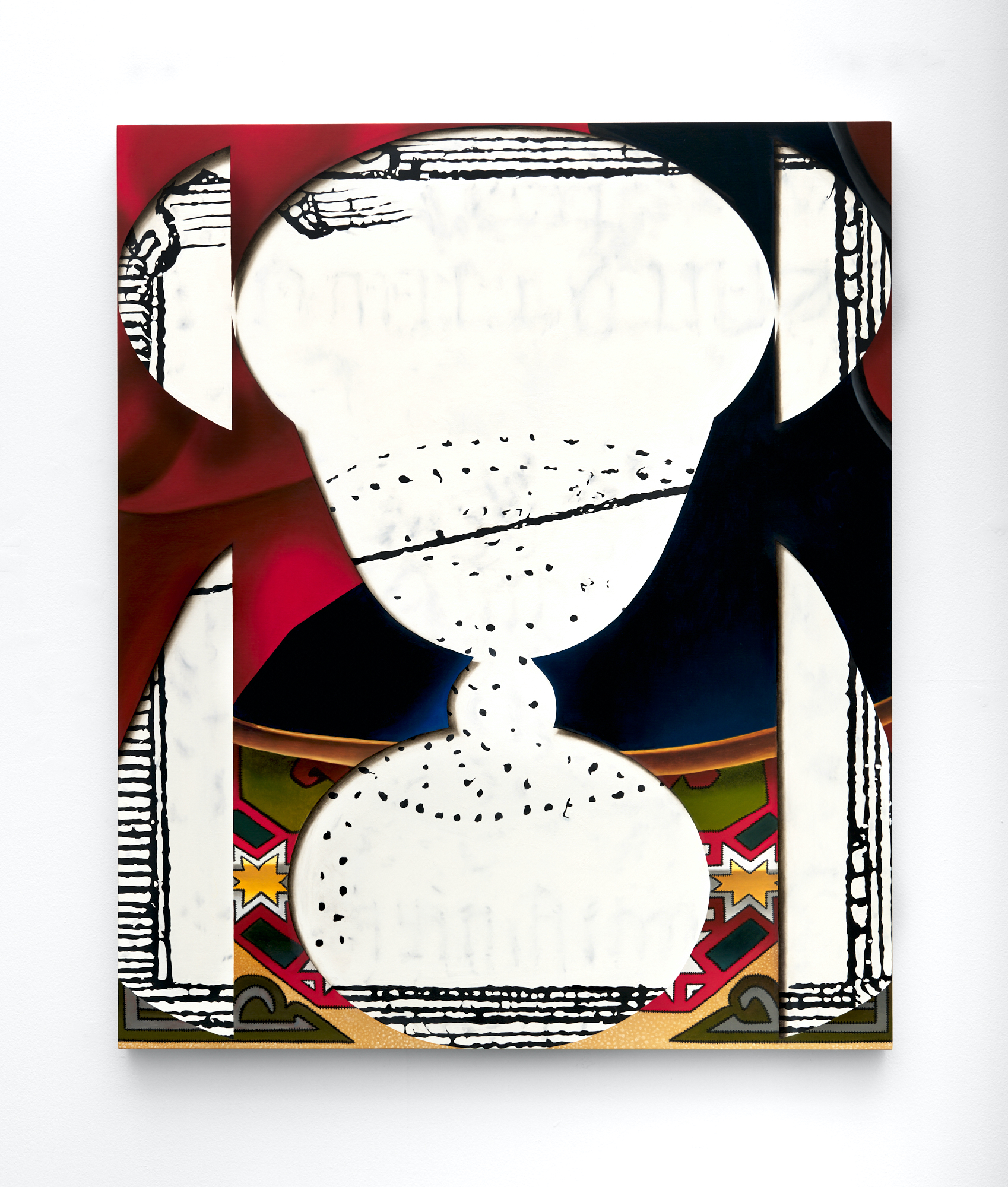

“Chalice (After Albrecht Dürer and The Master of the Morrison Triptych)” is based on a cutout detail from the middle panel of the Morrison triptych superimposed onto a detail from a Dürer work. The combination forms a white vessel with black details peering through the largely red and black overlay, reversing expectation that the cup is an object rather than the ground. While Halter’s reference to the triptych indicates that his chalice has a religious function, I would suggest that it serves as a ceremonial object, with no connection to specific religious belief or practice. Here Halter’s yearning appears to be for a community of like-minded painters.

I am reminded of a line that comes near the end of T.S. Eliot’s “The Wasteland”: “These fragments I have shored against my ruins.” Like Eliot, Halter believes that past works of art form a “tradition” that he must find a way to alter in order to make room for himself. Everywhere in Halter’s work, we see different kinds of alterations, from collage to copying “torn” fragments. These actions suggest that his work is not as cooly objective as it might first appear.

Evan Halter: Specificities continues at Turley Gallery (609 Warren Street, Suite 2, Hudson, New York) through October 27. The exhibition was organized by the gallery.