As the 1980s commenced, an unrivaled decade of cultural cross-pollination developed momentum in downtown Manhattan and Arthur Russell would produce consecutive releases suffused with its energy. He recorded these singles both with the aim of hearing them played through the seductively powerful sound systems of club spaces such as the Loft or the Paradise Garage and with the knowledge that dance records had the potential to be lucrative.

Article continues below

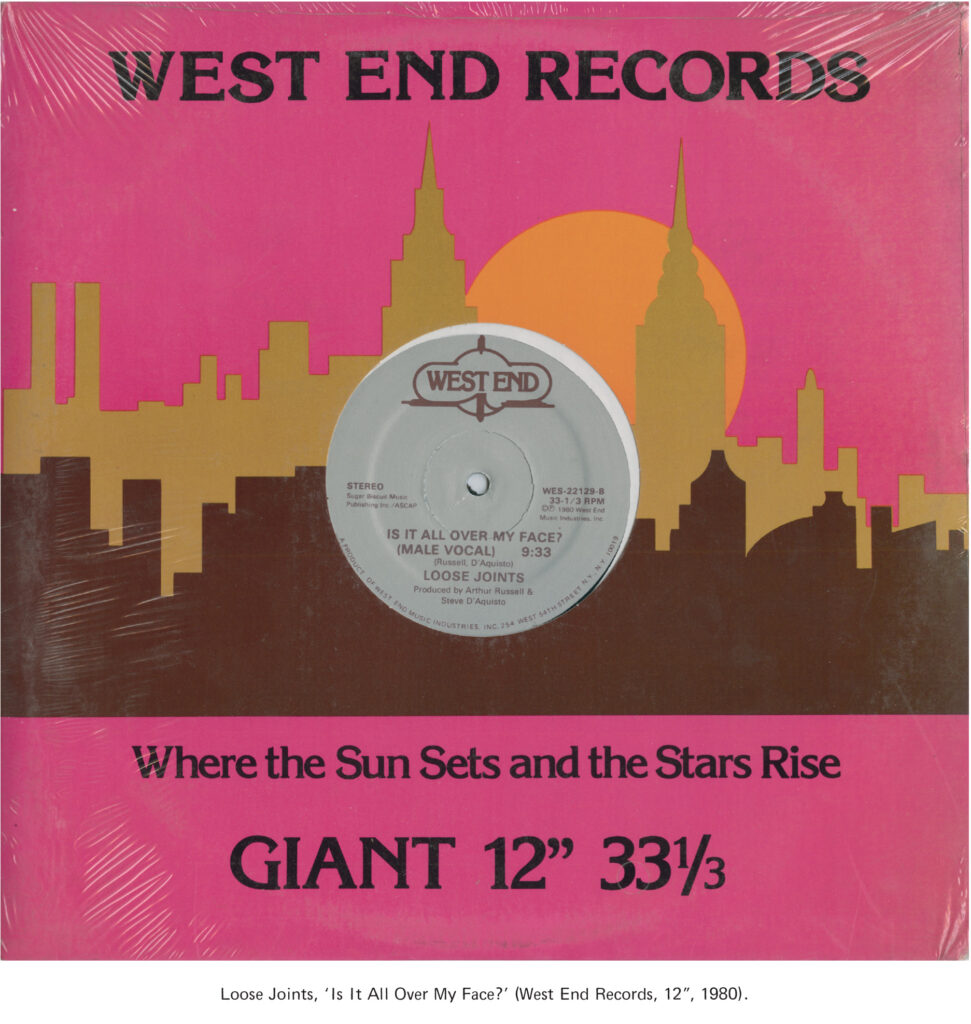

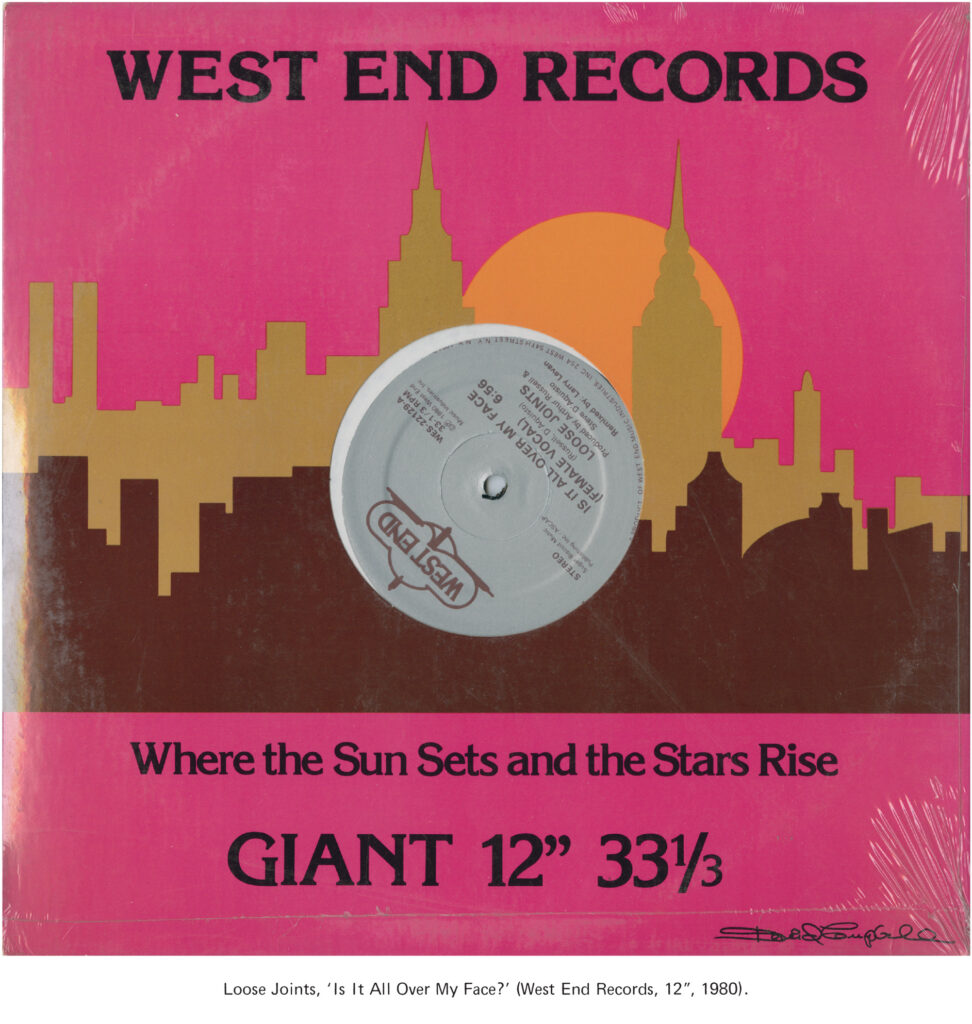

These tracks, which confirmed his reputation as an innovative and sui generis dancefloor producer, were released under various aliases: “Kiss Me Again” by Dinosaur was followed in 1980 by “Is It All Over My Face?” and “Pop Your Funk” by Loose Joints. In 1982 Dinosaur L (rather than the previous Dinosaur) released the epochal ‘Go Bang #5.’ Arthur would also utilize the names Killer Whale and Indian Ocean later in the decade. The decision to use such aliases was invariably a consequence of the fast-turnover street economy in which dance singles operated and Arthur’s mood on any given day. The changing names reflected both his capriciousness and music business expediency.

Mustafa Khaliq Ahmed: At the time I was working with James Mason, I was the percussionist on his album RHYTHM OF LIFE. While I’m recording with James, Arthur comes into the studio, because he worked about five or six blocks away at this place called Westbeth and this was down in the Village, but Arthur’s looking for spec time, he’s looking for all of these smaller independent studios to record his work. He comes into the studio and he’s there and he’s listening to a session that I’m working on. And this guy, he comes up to me afterwards: “Yo, I really like what you do, it’s like you’re the dude, you’re the dude.”

Now, I’m like a deer in the woods who comes out and there’s all these lights. I’m looking for opportunities to play. I had no formal music education and that’s how it was, and Arthur, he was very different to the R’n’B, jazz situations that I had been exposed to, and yet it was very exciting that he could hear my voice. That’s how we met: we met at downtown Studio, on Christopher Street, so that would have been about 1979.

*

In the late 1970s and for first half of the 1980s, Arthur’s dancefloor recordings shared a rotating set of musicians, as well as remixers. The foundations for Dinosaur L and Loose Joints releases was laid by Arthur’s favored studio rhythm section of the Ingram Brothers: Butch (bass), Jimmy (keyboards), John (drums), Timmy (congas) and William (guitar), most usually at recording sessions held at Blank Tapes studio in Midtown.

Here they were joined by collaborators and friends constituting alumni from the Kitchen/New Music confluence including Peter Gordon, Peter Zummo, Julius Eastman and Jill Kroesen; a group of musicians and composers with distinct individual careers who were content to play each other’s material, either in the recording studio or at concerts held in a network of clubs, theaters and performance spaces usually located downtown. The tapes of their work in the studio with Arthur were then passed on to a network of professional remixers for further collaboration, including such luminaries of mixing-desk dexterity as Larry Levan, François K. and Walter Gibbons.

Will Socolov: The music for those singles was done by the family from Philly, the Ingrams. They backed Patti LaBelle. The thing Arthur loved about the Ingrams is that it was a family. He said, “They vibe off each other, Timmy and Jimmy.” He said the most difficult to deal with was Butch, because Butch was older and he didn’t have the energy, he was like strictly business. Timmy and Jimmy, maybe Johnny, those guys, when Arthur would jam with them, he said those guys took off and they were really into it. Arthur I know loved to work with the Ingrams because he felt that they just worked together.

Peter Zummo: I was aware of the music as projects. In the studio, whether the session was called Loose Joints or Dinosaur, it could have been either. Dinosaur L took different forms and if that was the name of the band of the time, then that was the name.

I only had vague notions of what would happen with the recordings I just made or was making.

A name would be chosen—“This is Dinosaur L”—but the material dovetailed with other projects and bands from earlier and would be revisited in the future. That’s not an unusual process. It’s more creative than what a lot of people do. The process was just ongoing: working on the music, now we can play at the club, who’s going to play? What shall we call the band? The motivation was the continuation of the experiment. We were attracted to each other because musicians could do much more than render A to G on the score. What’s the next step?

Mustafa Khaliq Ahmed: I played with Arthur on sessions in Blank Tapes every now and then. But I’m not sure I was involved with him on the sessions for those singles, because the original Loose Joints were a group of studio musicians, the Ingram Brothers. They did the original stuff—Arthur hired them, however that happened; Arthur either had funding or something for them to do that. But those guys were not going to play in the little clubs and so forth and so on, because they were on a higher level, in terms of where they were, and so I’m the guy that came in to be the real embodiment of that, and once the Ingrams went on to their regular thing, that’s how he found me. He went out looking for guys to replace the Ingram Brothers. I had to learn all of the Loose Joints stuff and so forth.

Peter Gordon: I don’t know what the difference was between Loose Joints and Dinosaur L. I don’t think Arthur thought there was a difference. It was to do with business entities and record companies and things like that. I think it was similar to Parliament and Funkadelic—it was interchangeable. They were both working from the same raw materials. Whenever there was full moon Arthur would be in the studio one way or another. It wasn’t like they were special full-moon sessions, but he’d be sure to be working.

The sessions at Blank Tapes also featured Steve D’Acquisto, a charismatic DJ who had met Arthur at the Loft and was determined to see the music recorded in the studio released on a reputable label. D’Acquisto duly approached Mel Cheren of West End Records, arguably the premier record company in New York releasing music for the dancefloor.

Steven Hall: Steve D’Acquisto had the magic ear. Steve D’Acquisto could hear a hit: he had that ability, which in a way is a kind of genius which very few people have. I mean, usually people who have that ability end up running huge record companies.

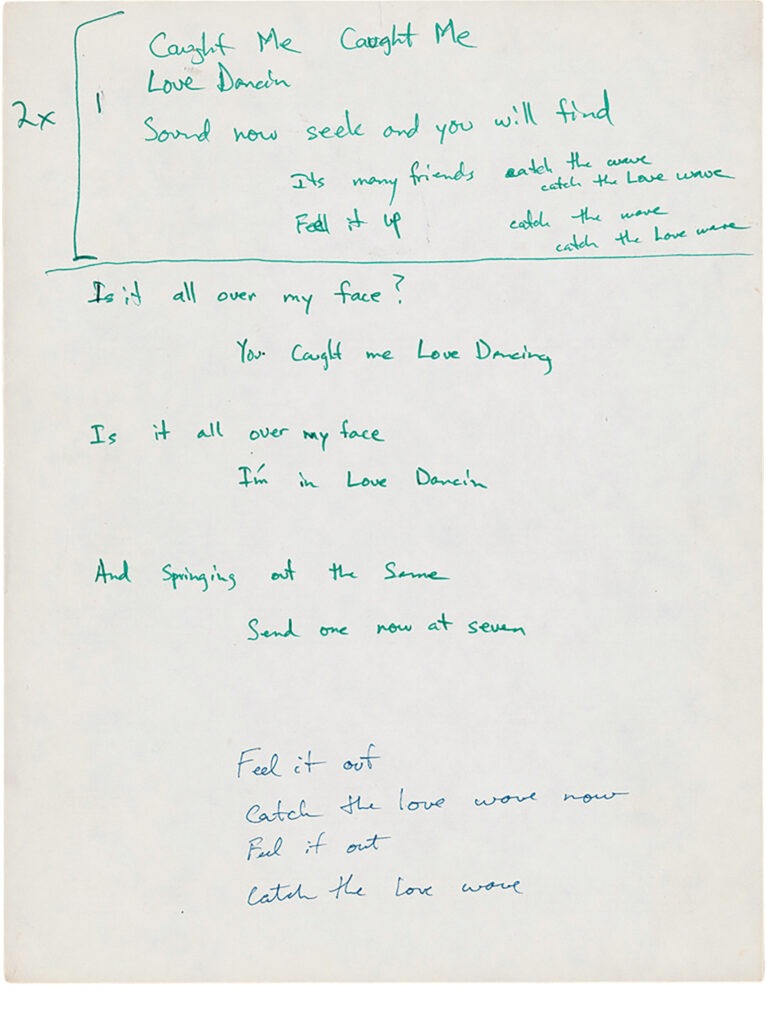

The studio takes for “Is It All Over My Face?” included a male and a female vocal version and numerous subsequently released recordings that evoke studio spontaneity verging on pandemonium. According to associates of Steve D’Acquisto, he would invite people he’d met on the street to visit the studio to participate in the musical energy. However, for all Arthur’s adherence to the philosophy of first thought, best thought—one D’Acquisto shared with a vivid enthusiasm—there was a foundational order to the recording sessions.

Peter Zummo: I didn’t see too much chaos in the studio. When I was there, there may have been a band or a rhythm section in the live room and I was stuck off in a corner, but often it was just me and Arthur. One time I was in his apartment either rehearsing or recording – I didn’t always know where it was going – when the phone rang and he came back in the room and said, “Now look, some really weird people are going to come up here now.” So I just waited and worked with the equipment. I don’t know who they were but they may have been some of the people who sang on “Is It All Over My Face?” All I knew was: “Are you doing anything Friday night? Can you come to the studio around eight?” There’d be music on the stand or there wouldn’t. Arthur liked it when it was getting out of hand because that’s when things get good, but that only happened because he set it up with many layers of process and the writing, recording and overlaying and happy mistakes. It was analog and we all wanted to see those little red lights lighting up and the needles going into the red.

I know people want to inject mystery and magic into the recording sessions but at some level it was just a skill, engaging in the process. Yes, we wanted to take it up a notch, we all wanted to get off, but the beat was good.

Lucy Sante: I was friends with Nan Goldin at that time, and I still sort of am, but I dated her for a week back then, and she was just starting to do her slide shows and one of the prize numbers she used was “Is It All Over my Face?” I thought this was the most amazingly explicit disco song I’d ever heard, and it was only later I found out it was Arthur, and I knew Arthur as this cello guy who played with Allen, seemed very peaceful, did not seem like the sort of person to put out this scabrous disco, you know?

Tom Lee: People infer a sexual element in the lyrics of “Is It All Over My Face?” But I always thought it was genuine joy. I remember it was a phrase Arthur and his father used, like—“Is it obvious?” Perhaps I was naïve!

______________________________________________

Excerpted from Travels Over Feeling: Arthur Russell, A Life by Richard King. Available via Anthology Editions. © 2024.