What is implied in the bold designation “Black revolutionary artist”? For Elizabeth Catlett, it encapsulates the way her life, legacy, and artwork together offer a blueprint for leftist Black feminist engagement with the arts. Anti-capitalism, feminism, anti-racism, and transnational solidarity are among the principles outlined in the analysis of Catlett’s politics in the catalog accompanying an exhibition of her work at the Brooklyn Museum. Edited by curator Dalila Scruggs, the book brilliantly illustrates how Catlett immersed herself in the formal and political possibilities of sculpture, drawing, painting, and printmaking.

A moving story underlies the title of Elizabeth Catlett: A Black Revolutionary Artist and All That It Implies. The African-American artist was born in Washington, DC, in 1915 and attended Howard University, but permanently relocated to Mexico after a 1946 trip to the capital city amid Cold War persecution of leftists. The United States government concretized her exile in 1970 by rejecting her visa to attend the Conference on the Functional Aspects of Black Art at Northwestern University outside of Chicago, an event that marked a turning point for the Black Arts Movement. Unwavering in her goal to address the conference nonetheless, she delivered a moving speech via telephone, in which these words stand out: “To the degree and in the proportion that the United States constitute a threat to Black People, to that degree and more, do I hope I have earned that honor. For have I been, and am currently, and always hope to be a Black Revolutionary Artist, and all that it implies!” Scruggs and other contributors seize this galvanizing moment as a point of departure, leading to explorations of Catlett’s commitment to 20th-century Black Power and leftist networks and the radical art she made along the way.

The book proceeds chronologically from Catlett’s training at Howard, early career in New York and Chicago, and exile in Mexico as a teacher and artist during the globalized 1960s. Each of the 12 chapters carves out a moment or idea formative to Catlett’s legacy, including parallels between sharecroppers and campesinos (working-class farmers), Black feminist representations of domestic labor, and the intersection of art and activism.

Even and especially after her exile, Catlett was dedicated to building transnational solidarity and artist-activist networks. At Taller de Gráfica Popular (TGP), the revolutionary printmaking studio based in Mexico City, Catlett continued making art honoring the work of Black American sharecroppers while drawing connections to the Mexican campesinos. As art historian Julia Fernandez explains in her essay on the topic, Catlett’s work contested “the othering of Black and Indigenous farm workers that stems from histories of enslavement and the encomienda system.”

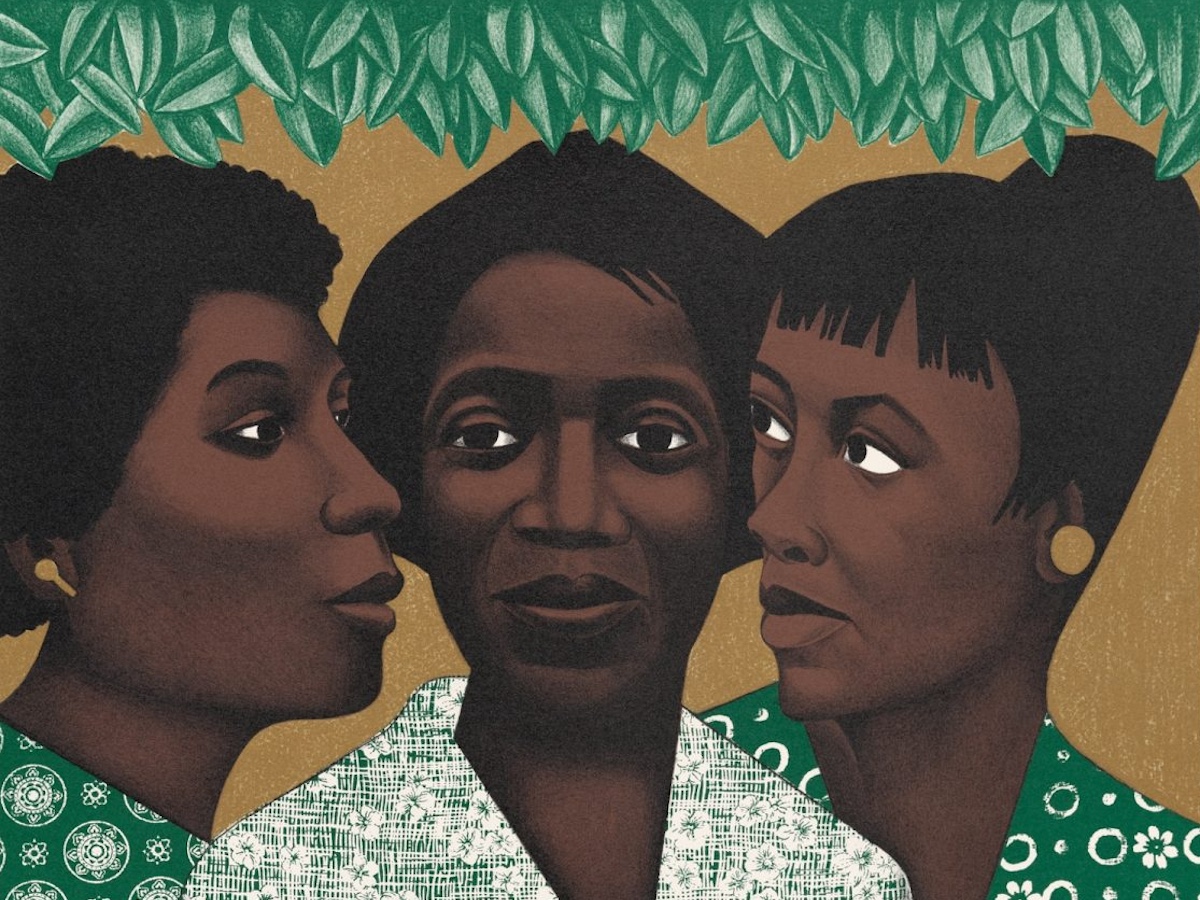

As she became acquainted with Mexican feminist politics, Catlett’s distinctly third-world feminist consciousness was a key element of her leftist worldview. She continually found ways to represent and honor Black American women despite moving to Mexico, keeping them at the center of her political consciousness and artistic production, as in her 1947 series The Black Woman. “Negro women in America have long suffered under the double handicap of race and sex,” wrote Catlett in a 1945 grant application.

Catherine Morris’s essay in particular sheds light on a moment of intergenerational Black feminist art history: In 1974, Catlett’s 1968 sculpture “Homage to My Young Black Sisters,” which she created in her Cuernavaca studio, was on view at the legendary Black art space, Just Above Midtown (JAM) gallery in New York. The sculpture is a life-size abstract representation of a woman with an outstretched Black Power fist in the air and an open space where her womb would be, whose display at JAM reflected cross-generational networks of Black feminist artistry.

From Chicano and Mexican modernism-inspired murals to publicly commissioned monuments, Catlett also closely observed and commented on the power of art to shape public space. Scruggs notes how Catlett’s public sculptures continue to animate public life today, from jazz concerts held at the Invisible Man-inspired Ralph Ellison Memorial (2002) in Harlem to the collective multitude depicted in the bronze “People of Atlanta” sculpture (1989–90) in Atlanta City Hall.

Catlett’s work as a radical educator was a natural extension of her political spirit, from Camp Wo-Chi-Ca to the National Autonomous University of Mexico. Scholar J.V. Decemvirale reflects on the “fugitive pedagogy” the artist enacted within the Black American and Mexican tradition, writing that her consciousness-raising and mentorship “resituated Mexican students into a broader decolonial worldview wherein the struggles of Black Americans were understood as part of the Third World’s anti-imperialist and anti-racist struggles.” Refusing Western formalist notions of teaching technical craft without political histories, Catlett diligently incorporated Black, leftist, and feminist lessons into her classrooms and workshops at the TGP.

Ultimately, this catalog is not only a gripping critical overview of Catlett’s impact on global art and activism — it is a necessary contribution to the rich, global genealogy of radical Black art histories. Catlett reminds us that identity alone doesn’t make one revolutionary; actions in pursuit of our shared liberation are just as crucial.

Elizabeth Catlett: A Black Revolutionary Artist and All That It Implies (2024) is published by the University of Chicago Press and the Brooklyn Museum and is available online and through independent booksellers.