LONDON — The Decay of Beauty. The Beauty of Decay, a compact but ambitious exhibition at Colnaghi Gallery, examines the concept of beauty and its inevitable decay across pan-historical, pan-geographical, and pan-religious examples. The show spans ancient Rome and Egypt, Tibetan Buddhism, and Christian-inflected vanitas, through to contemporary art. Such wide scope in a commercial gallery could be easily read as a calculated scheme to sell disparate or unusual artworks. Yet independent curator Alfred Kren originally intended the concept for a museum. In finding a home in Colnaghi, Kren has garnered significant privately owned works for the project, not least a magnificent 10th-century Indian three-headed bust of Chamunda from the collection of Anish Kapoor.

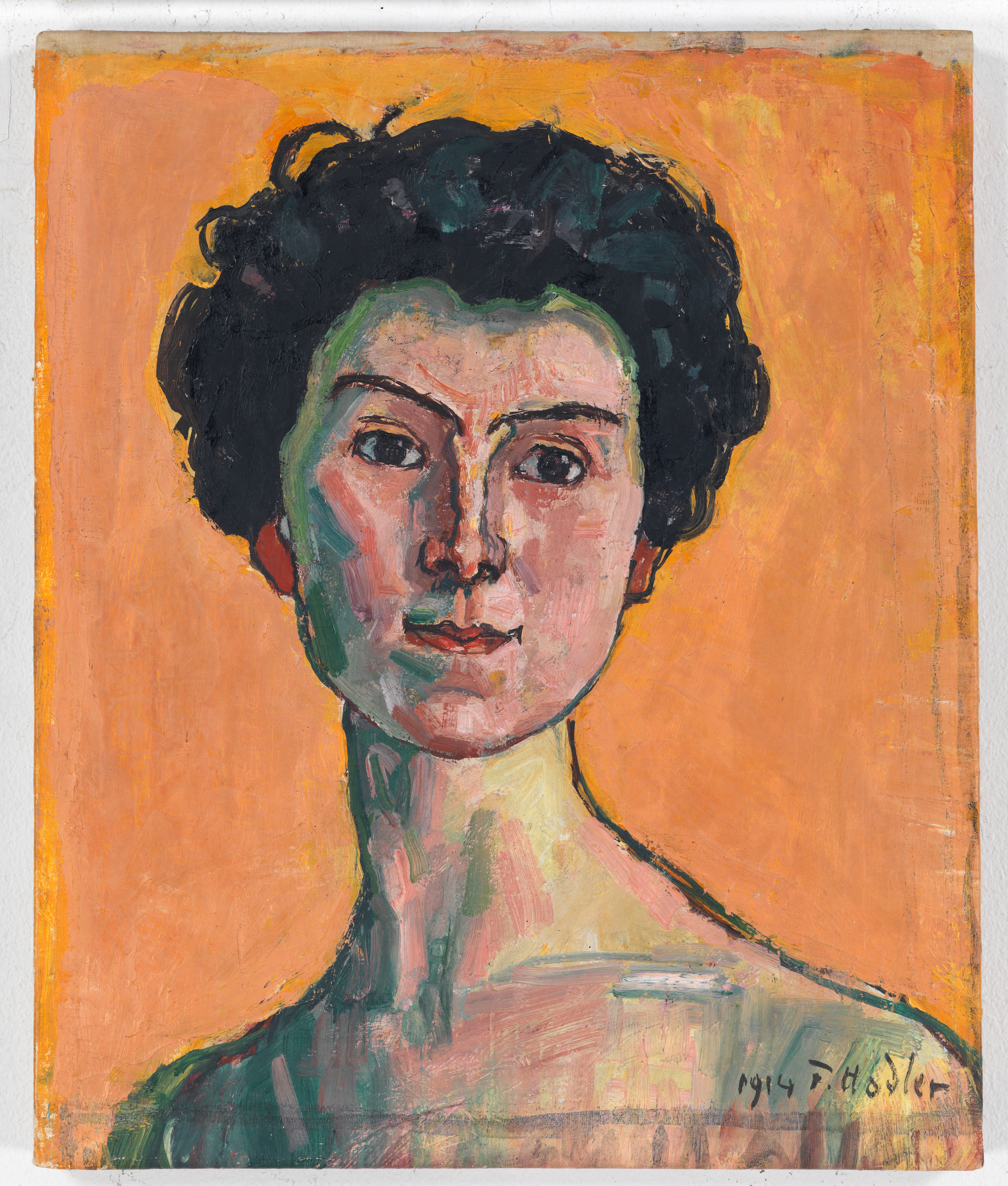

Any attempt to identify deliberate iconographic or stylistic similarities between works of such disparate times, locations, and creeds is a pointless exercise of finding flukes. Instead, pleasure may be found in the contrasts and juxtapositions within single vistas, complimented by the intimate Colnaghi viewing space and the exhibition’s overarching sensibilities: temporality, even ghoulishness in the notion of decay. A curious inclusion is Swiss painter Ferdinand Hodler’s “Portrait of Clara Pasche-Battié” (1914), perhaps the only piece in the show solely concerned with capturing aesthetic beauty. Surrounded by art that dwells on decay and mortality, it takes on a forlorn tone.

In one grouping is Frans Francken the Younger’s painting on copper, “Death and the Miser” (undated). The cautionary work shows a looming, loin-clothed skeleton playing a fiddle to a surprised elderly man with material wealth. Next to it is an extraordinary 19th-century Mongolian Citipati wherein two skeletons representing wrathful deities signify the eternal dance of death, and a painted 16th-century Kapala from Tibet, a ritualistic skull cap apparently made from an actual human cranium. Each differs in purpose and execution, exemplifying the varied attitudes toward death in their respective cultures, and yet each invokes a kindred feeling of unease, or even fear. Similarly, a scholar’s rock from China (17th–early 18th century) is placed alongside Catherine Murphy’s “Swept Up” (1999), a minutely detailed pencil drawing of floor detritus swept into an unceremonious pile. Their shared grayscale textures and jagged points and irregularities formed by the chaos of nature reveal a curious visual commonality between wildly dissimilar pieces, highlighted by curatorial placement.

The theme of beauty and its decay is most concentrated in a small backroom containing Catherine Murphy’s oversized, confrontational close-up painting “Harry’s Nipple” (2003), paired with a Roman statue of Asclepius — a typical example of the idealized body — along with a tiny study of a female nude by Fantin Latour (undated), and a zingingly pink, highly abstracted figure by Maria Lassnig titled “Blasser Nachtgeist” (Pale in Spirit, c. 1990–99). By bringing together such diverse and extreme treatments of bodily representation, the show suggests that our attempts through history to identify and capture idealism in the human form have long been unsettled and troubled.

It is perhaps fortunate that Kren’s idea landed in Colnaghi’s gallery spaces rather than an institution, for this quietly but profoundly affecting collection of works may have lost their power when expanded in number. Such ambitious scope works here precisely because of its concentration. For once, a conceptual gallery show sets sales aside and remains refreshingly focused on the concept.

The Decay of Beauty. The Beauty of Decay. continues at Colnaghi Gallery (26 Bury Street, London, England) through November 8. The exhibition was curated by Alfred Kren.